JUST ANOTHER DUMB ASIAN SINGER

I have a vivid memory of my parents taking me to see Midori perform at Hill Auditorium in Ann Arbor, MI. I was about 9 years old, and a group of local Suzuki violin students went to see this prodigy, who had already catapulted to international fame by the time she was our age. When we saw her, she couldn’t have been more than 17. I was completely captivated by her mastery of the violin: a universe away from my clumsy half-hours of begrudging, required practice of the simplified classical tunes in my Suzuki violin book. I remember her playing the Beethoven concerto and wishing she would play the Tchaikovsky, my favorite. I also remember the white people around me criticizing her playing. They wondered aloud about the emotional and expressive depths of her artistry and more than one white concertgoer in my earshot described her playing as “robotic”.

Fast forward another 9 years and I had left the violin behind, discovering that my calling was to voice and not to violin. I had lucked into a relationship with a voice teacher and mentor who believed in my talent and laid down the artistic and technical foundations that underpin my work to this day. She was a white liberal who cared about social justice so I knew that her racism was accidental when, one day, we were polishing some songs for an upcoming performance and, in an attempt to encourage me to be more communicative and emotionally engaged with the music, she told me that some Asian singers had trouble using their faces expressively on stage.

When I was young, I didn’t see these (and many other) incidents for what they were. I was shielded from these dynamics by the relative privilege of my middle class upbringing in a college town. Still, as I have often mentioned in other various forums, growing up in Southeastern Michigan I didn’t see very many other Asians. Mostly, I was surrounded by white people, and racism was discussed and taught as discrimination that targets Black people.

Throughout the 7 years of my middle school and high school education, the history and social studies curriculum I was required to navigate attempted to ensure that all of the school’s students had a general survey of world history before graduation. Two of those seven years were devoted to American government and history. At our private college prep school, considered one of the region’s best, people of Asian descent made minimal appearances in my pre-college history education. They first appeared as we briefly covered the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor, which was framed as the reason the US entered World War II before shifting focus completely to the European theater of the war. The only other appearance in any of those classes or textbooks was in discussion of the Vietnam and Korean wars. These wars were described through the narrative of two predominantly white nations waging a “cold” war with each other. The Asian inhabitants of the countries in which these wars were being hotly waged were dehumanized herds who were impossible to tell apart from each other as they were incinerated with abandon. Asian leaders were described as the “puppets” of the white American and Russian politicians of the time. Any other discussion about these wars was focused on protests for peace led by white people here in the United States.

1882 political cartoon showing a Chinese man being barred entry to the "Golden Gate of Liberty" with the caption “Enlightened American Statesman: We must draw the line somewhere, you know.” SOURCE: Wikipedia

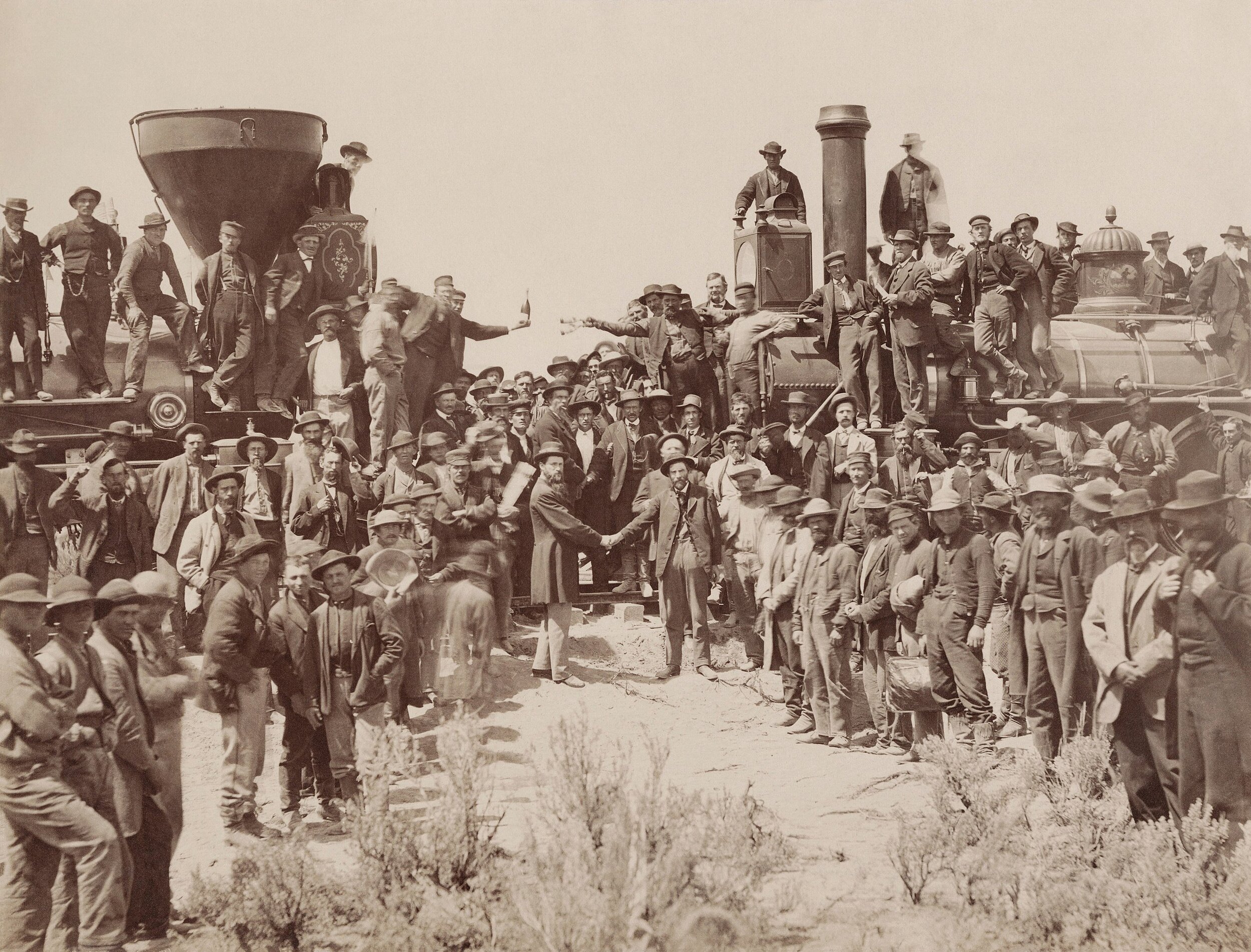

Much like the famous photo taken of rail-workers celebrating the completion of the First Transcontinental Railroad, which only shows white faces and none of the faces of the thousands of Chinese “coolies” who did the majority of the labor to construct the railway which connected American East to American West for the first time, the Asian-American experience was largely erased from the version of American history I was taught. I learned about the many glories of our white founding fathers and presidents, I learned about Jim Crow and the history of slavery in America. I heard not a word spoken about the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. Barely a syllable spoken about Japanese internment camps in World War II. The first-born son of a Chinese man who immigrated to the US from Indonesia, I took this to mean that Asians had not appeared in America until only recently. I internalized a sense that, as an Asian American, I was more Asian than American – that our stories were not the stories of America. I would not begin to deconstruct these beliefs and realize the full extent of my own American-ness until I would represent the United States at the BBC Cardiff Singer of the World competition at the age of 24. This alienation was the result of gross omissions on the part of American education, but I would not recognize it for the racism and xenophobia it was until much later. In my young mind, racism was something white people did to Black people.

During my senior year of college, while researching options for graduate school, I took a trial lesson with a voice teacher named Nina Hinson in Los Angeles. A Chinese-American soprano friend of mine had been studying privately with Nina while she was living in Southern California that year, and she highly recommended her as a teacher. I made plans to visit her around New Year’s, combining my school-research trip with a much-needed escape from one of Michigan’s brutal winters. After a day or two enjoying the beach and celebrating the new year, my friend introduced me to Nina. Toward the end of our session, Nina advised me to change my last name to my mother’s Greek maiden name so that judges and casting directors wouldn’t assume that I was “just another dumb Asian singer”. I was too shocked by her comment to know how to reply, as was my friend who was sitting just a few feet away on the couch, observing us work. Put into the context of the framework with which I understood racism at the time, I wrote it off as an outlier experience and just assumed she was a wingnut. I didn’t really become fully aware of how rampant anti-Asian racism was until I moved to New York City, where, for the first time, I was surrounded by more people who looked sort of like me.

After leaving the University of Michigan and my childhood home of Ann Arbor, I spent a summer at the Glimmerglass Opera as a young artist. There were only two other Asian singers out of the 25 in the young artist program that summer, another half-Asian tenor who has since retired from singing, and a Korean soprano who has become a lifelong friend and now sings in the chorus of the Metropolitan Opera. This was not strange to me, as I was used to those kinds of numbers and representation from my experiences at home in Michigan. Right after Glimmerglass, I moved to New York City to begin a Master’s of Music in opera at the Manhattan School of Music.

DOROTHEA LANGE: “Oakland, Calif., Mar. 1942. A large sign reading "I am an American" placed in the window of a store, on December 8, the day after Pearl Harbor. The store was closed following orders to persons of Japanese descent to evacuate from certain West Coast areas. The owner, a University of California graduate, will be housed with hundreds of evacuees in War Relocation Authority centers for the duration of the war.” SOURCE: Library of Congress

When I entered MSM in 2001, the school was flooded with Asian students. Immersed in an environment with fellow Asians, I soon began to witness just how blatantly racist opera and classical music can be towards Asians. It was not uncommon to hear non-Asian students say things like, “oh yes – they take all these Korean students, because they know they can pay the full tuition – how else do you think they keep this place afloat?”, as if this somehow explained how there were so many Asian singers in the voice program at MSM, but so few of them were selected for one of the coveted spots in the Opera Workshop class.

For those who made it into the Opera Workshop, it wasn’t much better. Fully Asian students were often spoken to in slow, condescending (and not infrequently loud) tones by directors who assumed that they did not understand English. In my first and only semester in the opera workshop class at MSM, I was cast as Fenton opposite a wonderful soprano from Korea as Nannetta in the notoriously challenging Act I, scene ii of Verdi’s Falstaff. One very tense morning we were staging the duets from that scene. The white stage director, who was also the head of the Opera Department at the time, kept making us repeat a certain bit of staging over and over, repeatedly sniping corrections at my soprano colleague in a brusque, aggressive, condescending and impatient tone, as if he was speaking to a 4 year old and not a 25 year old adult woman. After 20 tense minutes of this, he threw his arms up in the air and looked at me, exclaiming, “she just doesn’t get it!” as if she couldn’t understand the English words he was saying about her right in front of her. He then left the room to tend to an issue which had arisen in another rehearsal that was happening at the same time. I was left to console my colleague, reassuring her that she was, indeed, “getting it”, that she sounded beautiful, and that we could still have a productive rehearsal and make our scene beautiful in spite of this man’s xenophobic and racist ass-holery.

I only stayed on at MSM for one year, before I was recruited to join the Houston Grand Opera Studio, where I would apprentice full-time for three years. As I entered the professional young artist world during these final years of my education and early years of my professional career, I again felt I was in the familiar racial landscape of my childhood. In the five years I was embedded in young artist programs at HGO, Glimmerglass and Wolf Trap, I performed alongside a total of 5 Asian soloists: countertenor Brian Asawa, mezzo-sopranos Zheng Cao and Mika Shigematsu, and baritones Earl Patriarco and Chen-Ye Yuan. I auditioned only for white opera casting directors and met only white artist managers. I observed from afar as Nina Hinson became the primary voice teacher for the apprentices at the Santa Fe Opera. Towards the end of my first year at HGO, I was cast in the comprimario role of Gastone in Verdi’s La Traviata. At our first rehearsal working together, the director of the production, Frank Corsaro, a veteran of the opera world and the head of the opera department at the Juilliard School at the time, asked upon meeting me: “What are you? Because you certainly aren’t white.”

As I deepened and expanded my knowledge of opera history while immersed in training at the opera house, I listened to historic recordings and watched historic films of mostly white opera singers, with the occasional Black operatic superstar thrown in. I looked around and did not see many people like myself anymore. If I did, they were playing in the pit, or they were the occasional stray Asian chorus member. I only remember seeing two Asian singers appear on any opera recordings during those years: Sumi Jo and Hei-kyung Hong. Time after time in the first decade and a half of my career, I would see one white singer after another praised for their artistry. When I saw any singer of color praised, it was for their athletic capabilities: the size of their voice or how they could tackle virtuosic bel canto music with “superhuman” ease. Their artistic intelligence was either ignored or presumed non-existent.

In 2007, I was afforded the opportunity to spend the first of four summers at the Marlboro Music Festival. A haven for chamber music and musical meditation, the festival is primarily populated by instrumentalists. Singers are the rare and mysterious birds at Marlboro, and the musical environment there is a unique one. Because there are no conductors nor music-staff intervening between singers and instrumentalists in a chamber music setting, there is the opportunity for both types of musicians, who often relate to music in radically different ways, to learn from each other directly.

Having spent most of my childhood and teenage years dreaming of becoming a professional violinist, I felt reconnected with my childhood. This first summer at Marlboro marked a significant shift in my career trajectory, during which my calendar would begin to fill with more concert and recital engagements, resulting in fewer operatic ones. This return to a community primarily filled with instrumentalists also meant that for the first time since my single year at MSM I was surrounded by a great number of people who looked like me.

Look at any modern US orchestra, and you will see that there are many Asians in classical music. Herein lies a significant difference between classically trained instrumentalists and singers: Asians have broken down many barriers in the orchestral world. We are dramatically better represented in the instrumental world than we are in the operatic world, where our numbers are arguably even fewer than our Black and Latinx colleagues. Take, for instance, the Metropolitan Opera’s recent At-Home Gala, in which the only east Asian soloists featured were not singers, but two violinists from the orchestra. I would argue that this is due in part to an industry standard in the United States to hold auditions behind a screen for most of the rounds one is required to successfully navigate in order to secure a position in one of these US orchestras. No such standard exists for voice auditions, where subjective and easily racialized traits like “stage presence” and “likability” are a bigger part of the selection process.

People react to this orchestral diversity in two ways when assessing the state of inclusion in classical music. One is a general whitewashing of Asians in orchestras. It’s not uncommon to see music journalists clumsily attempt to discuss racial inequities in classical music under headlines like “It’s Time to Talk About Classical Music’s Diversity Problem” or “Why is American Classical Music So White?”. In the first article, the journalists first group Asian musicians in with white ones, as if Asians are in the same category of privilege and are not musicians of color: “Despite the enormous influence of musicians of color on nearly every genre of music, the classical music field remains starkly white and Asian…”. They then go on, just one paragraph later, to again erase Asians from the picture as people of color: “…Not to mention the profoundly discouraging reality that many musicians of color face when attending their first classical performance — looking up at the stage and being unable to spot a single player who looks the way they do…” Failing to fully understand all the dynamics of diversity at play, while attempting to engage in a discussion about racism, the article itself becomes racist, obfuscating the discourse.

When we’re not simply ignored by being grouped in with white people, Asian contributions are minimized. I’ve more than once overheard a person exclaim “wow! There are so many Asians in the orchestra…” with a sense of shock and a hint of xenophobia in their voice. Our presence in the classical music world is often explained away by a cursory mention of Asian insistence on music education, paired with the racist assumption that all Asians are wealthy, highly educated, and have a genetic machine-like work ethic that gives us some sort of unfair advantage. This kind of thinking is akin to the argument that because we have finally had a Black president, anti-Black racism is a thing of the past.

An Illustration from an 1869 edition of Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper depicting an Irishman throwing a Chinese man over a cliff and Southern plantation owner leading him to the cotton fields. SOURCE: Library of Congress

The ceremony for the driving of the golden spike at Promontory Summit, Utah on May 10, 1869; completion of the First Transcontinental Railroad. SOURCE: Wikipedia

Anti-Asian racism comes in many forms and, in the United States, enjoys a complex history. Aside from general ignorance of the Asian story in America from the mid-1800’s through the middle of last century, the most common contemporary trope is that we are all highly-educated, hard-working, upper middle class or higher, success stories of immigrant families that came to this country “the right way”. These tropes are what buttress the many jokes made about the Asian anti-affirmative action case brought against Harvard, which in reality was led behind-the-scenes by an ultra-conservative white man with a racist agenda. It’s behind the stereotypical image people hold of Asian children taking Suzuki lessons and learning to play violin as if it’s some east Asian right of passage for every child with a Tiger parent, a term that makes me deeply uncomfortable. While it was coined by an Asian author, it strikes me as racist that Asian parents who sternly make their children practice are compared to animals, while the overbearing white moms who are overinvolved with their children’s performance activities are called “Stage Parents”. We are praised for the perceived hard-working qualities of our “race” that enable technical virtuosity, yet are commonly accused of lacking artistic and emotional depth. The “authenticity” of our interpretations is either questioned or – no less offensive – is framed as a marvel because of the fact of our non-European faces. The poet and author Cathy Park Hong describes this dynamic in her book Minor Feelings, “we have a content problem. They think we have no inner resources.” Perhaps this is why you see so many Asian faces filling the ranks of orchestras, but it is much less common to see an Asian adult standing in front of orchestras as soloist or conductor. Just like our brothers who were excluded from that Transcontinental Rail photo over 150 years ago, our hard work is welcomed, but we are not invited to be part of the photo op .

Asian musicians, particularly in the instrumental and symphonic world, sometimes enjoy a basic privilege that many of our Black, Middle Eastern, and Latinx colleagues are not often extended: seeing more than one other person who looks like us in the room. Nonetheless, we face racism and have had to overcome xenophobic prejudices in order to be taken seriously as musical artists and, like our other colleagues of color, we are barely represented in the administrations making the hiring decisions. In the nearly 20 years I’ve been a professional singer, out of the roughly 200 classical music organizations with whom I have worked, I have been hired by only eight Asian artistic administrators in the United States: one who used to be at the New York Philharmonic, one at the Philadelphia Orchestra, one who used to be at San Francisco Performances, one at the Celebrity Series of Boston, two at the University of Chicago Presents, one who used to be at Da Camera of Houston, and one at a regional opera company that dissolved over a decade ago. I’ve been hired by only one black artistic executive, who used to be at the San Francisco Symphony and is currently at the Cleveland Orchestra. To my knowledge, I have never been hired by a non-white artistic administrator or casting director in Europe. Of the almost 100 conductors I’ve collaborated with, only four have been Asian: Alan Gilbert, Jahja Ling, Zubin Mehta and Masaaki Suzuki. One has been black: Thomas Wilkins. Only five have been women: Marin Alsop, Karina Canellakis, Joann Falletta, Jane Glover, and Jeannette Sorrell. Only 12 of those conductors have been openly Lesbian, Gay or Bisexual.

American classical music is not ‘all white’. Just look at any orchestra and count the East Asian faces. There are serious issues of diversity, equity, and inclusion in classical music that must be addressed, and anyone who has amassed any power in our industry needs to work in solidarity with all communities of color to bring about these changes. While we discuss issues of racial inequity in classical music, please stop whitewashing Asian contributions. To do so is racist. It is ignorant of the complex and terrible history our people have faced, and it grossly minimizes the importance of the presence we Asian musicians do have on classical music and opera stages.

James D. Phelan’s campaign advertising

I now live in San Francisco, where the classical music and opera scene is largely housed in the city’s War Memorial complex. The oldest buildings of the War Memorial (the Herbst Theater and the Opera House) were some of the last to be built in the Beaux Arts style in San Francisco, a trend begun by San Francisco’s mayor at the turn of last century, James D. Phelan. Phelan was passionate about bringing the “City Beautiful” movement’s ideas into the city’s planning and fortifying San Francisco as a cultural and artistic capital. Phelan infested State and National politics for over 2 decades at the turn of last century, ultimately rising to the rank of U.S. Senator from 1915-1921. For most of those decades, the primary platform upon which he was elected was his vehement anti-Asian activism. Running on a campaign to “Keep California White”, specifically aimed at adding Japanese exclusion to the Chinese Exclusion Act, Phelan was vaulted into the hallowed halls of the U.S. Senate, where he was instrumental in expanding the Chinese Exclusion Act to all Asian immigrants. In large part due to the xenophobic paranoia he fomented during his lifetime, atrocities like the Japanese Internment camps of World War II would be deemed acceptable, and exclusion would not be repealed until 1943. Substantive attempts at real anti-racist change on the immigration front would not occur until the Immigration Act of 1965.

Each and every time I walk onto any of the War Memorial stages, knowing that the arts scene in San Francisco was so important to James D. Phelan, I feel something akin to the many protestors who are out on the streets, tearing down confederate monuments and statues of white colonizers and slaveholders. I rejoice in knowing that a young Asian person might be in the audience, at their first classical music concert, not only seeing me, but also my many fellow Asian colleagues sharing the stage with me. I wish the rest of America could see us, too. Our presence represents important progress, not to be ignored, nor taken for granted. There is so much further to go, but we are here. Together, we will play, sing, struggle, strive, create, and build a better world.

This post is dedicated in gratitude to Brian Asawa, Zheng Cao and Mika Shigematsu, all taken from us too soon. I will never be able to thank them enough for showing me what was possible by just being who they were.